Because of the Covid-19 pandemic, hundreds of thousands of seafarers have been stuck offshore due to crew relief issues. They are left to their own fate as international institutions have a hard time harmonizing maritime law.

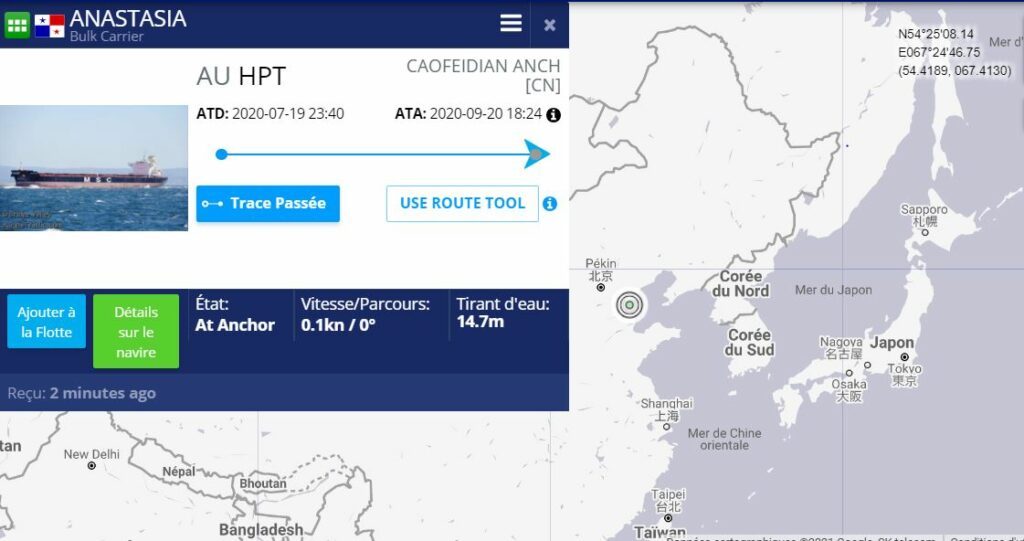

From his boat cabin, where he has been spending most of his days for 5 months now, Gaurav Singh looks exhausted. His fingers and skin are bruised by infections, due to the “quality of the water” and he has troubles moving his leg. He is the deck officer of the MV Anastasia, a cargo boat stranded near China. The sailor is one of the 16 seafarers, mostly from India, trapped on this vessel. He feels that he and his crew are turning mad, day after day.

The Covid-19 pandemic did not spare the oceans. Seafarers which are responsible for 90% of the maritime trade, have suffered from closed borders.

In October, the UN reported that 400,000 sea employees were stuck offshore because of the pandemic as they were « unable to disembark at the end of the journey ». According to Human Rights at Sea NGO, the ordeal of hundreds of sailors lasted more than 17 months, far from the 11 month’s limit set by international labour standards.

On December 8, 2020, a motion from the International Labour Organisation (ILO) requested that member states recognize seafarers as « essential workers » in order to facilitate their transit period, highlighting the need to « guarantee safe crew reliefs ».

“We have been living in this boat for about 19 months”, says Gaurav Singh with regret. His cargo boat is one of the 70 ships estimated to be stuck in the Yellow Sea since August 2020. Most of the boats have not been yet allowed to discharge their shipment in Chinese harbours: 10 millions tons of Australian coal. China has cited various factors like the coronavirus and environmental issues to stop the operations. This standoff has raised tensions between Beijing and Australia, since Australian authorities urged for an independent investigation into the origins of the covid-19 pandemic.

Physical and mental issues

In the meantime, seafarers have been exposed to hard life conditions. Physically affected, the crew of the MV Anastasia is still waiting for medical assistance. According to Gustav the crew requested information from the Chinese authorities. “They replied that they won’t provide medical equipments nor doctors unless someone is on his deathbed”.

On-board, sailors aged between 50 and 60 years, are suffering from blood pressure issues or diabetes. Some are “unable to move their hand anymore”. Gaurav Singh presumes that other boats face the same difficulties but it is hard to estimate the magnitude of the despair as there are limited means of communications in some of them. “Only two or three stranded ships have internet facilities. The others are totally cut off from the rest of the world”, the MV Anastasia navigation officer reckons.

“They sit in their cabins, and think about what they are missing all day long. This affects their mental health. One of the guys tried to commit suicide. He said that if he were to die, his body will finally reach his family ».

The Indian sailors are not the only ones suffering from the consequences of the pandemic at sea. The whole maritime industry has been affected. Mentally exhausted, without any medical care, suicides, sexual assaults and murders have increased in seafarers crews. According to David Hammond, CEO of Human Rights at Sea, seafarers’ work conditions are a form of modern slavery: “People do not understand the situation they are in. The workers are slaves to earning money. It’s a form of servitude.”

“If we try to move the ship, China will arrest us”

The main issue is that crew reliefs are not taking place. In 2020, shipowners canceled these manoeuvres, reckoning that Covid-19 pandemic would be short-lived. Contracts of seafarers have been extended, preventing them from disembarking. They had to work longer with a higher risk of accidents. Pierre Blanchard, president of the French Captain Association (AFCAN) sailed for 5 months instead of 3, in 2020. He feels lucky that he was able to come home safely : “It was tough for all the crew, we take risks when we navigate gas-carriers. There is no room for mistakes. It is a miracle that everything went well”.

According to Jean-Philippe Chateil, general secretary of the Union of the officers of the French Merchant Marine, throughout Covid-19 pandemic, “hundreds” of French sailors have been stuck all around the world despite contract obligations expiration.

They sailors have to follow the laws of the Vessel’s flag, regardless of their nationality. These laws differ from one flag to the other, and from one ship to the other.

Registering a vessel under “convenience flags” as are Panama, Liberia or Bahamas, provides several advantages to the operator such as low taxes, cheap international labour, less administration controls or few labour laws. As a consequence, 63% of the worldwide fleets sail under this flag.

According to Chateil, compagnies sailors under French Flag during the pandemic were able to organise safe returns. “As they saw things dragging on, they chartered planes from Congo, from Algeria, where they organised secure landing hubs for crew relief”.

On the other hand, he says that the way convenience flag’s managed these operations were “catastrophic“. As for seafarers, living and working conditions on board are especially precarious, and, according to him, shipowners do not hesitate to offer them contract extensions because “they know they will accept them”.

European sailors are mostly preserved from abuses because “owners know we are taking actions”, he explains, regretting that seafarers from the Philippines and China could not protest for fear of losing their job.

A land issue, more than a maritime one

For Professor Patrick Chaumette, maritime and oceanic activities expert from Nantes University, states mismanaged this crisis. “In the EU, it took 5 months before it was finally recognised that some supply problems could arise. We did not realise that we were that dependent on seafarers”. States were very slow in setting “sanitary corridors” for seaworkers to join airports, for instance.

Pr Chaumette compares seafarers’ conditions to lorry drivers: “invisible workers until they start demonstrating. Their are no international authorities that are qualified to control how long workers remain on the job even though to law forbids to extend this period above 11 months. If seafarers are trapped offshore, the attempt to sue companies, in order to repair damages caused by prolonged isolation, could be difficult and imply taking collective appeals via international organizations.

“Legal tools exist, but they are mostly theoretical and the situations are very diverse”, Pr Chaumette says, especially aboard convenience’s flag vessels. Picturing an international law system which preserves seafarers rights and freedoms seems to be a fantasy while some countries deliberately play with sailors’ life to serve political interests.

Pr. Chaumette gives an example: “China has already used « visa policy » as a diplomatic weapon using retaliatory measures forcing European sailors, sometimes French, not to land”. Despite hopes to harmonize legislations across the world, international organizations’ efforts seem to be powerless.

The limited power of the ILO

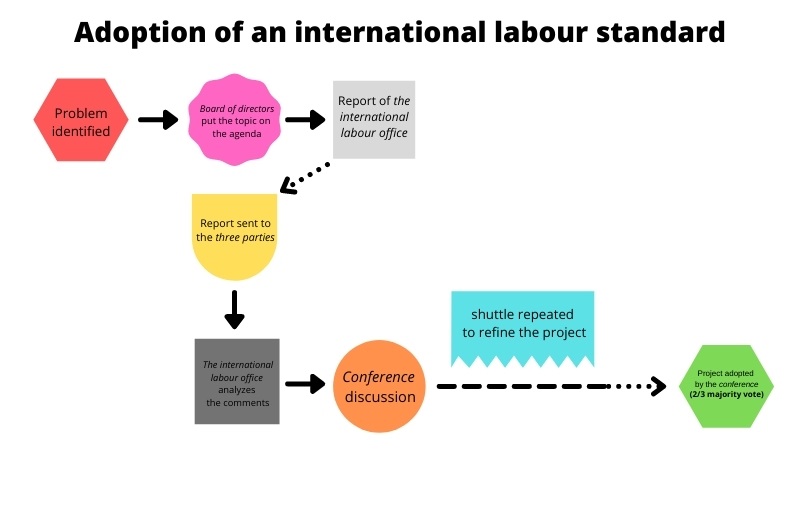

To fix this legislative chaos, the International Labour Organization (ILO) is working on harmonizing the rights of seafarers. It send out recommendations, the most important of which is the MLC (2006), the maritime labour convention, an agreement that frames maritime labour.

This convention complements the texts of the International Maritime Organization (IMO) concerning the safety and security of ships and the protection of the marine environment.

This text establishes working and living conditions for seamen. It aims to harmonize the rules and rights of seafarers onboard. As Charles Autheman explains : “The ILO is an organization that produces standards, but above it is a venue for debates on international labor standards”. ILO’s divisions and offices all over the world allow the organization to have an influence on strategic decisions in some states. “It is a decentralized organization. With its regional offices, the ILO also operates more strategically and in bilateral dialogues.”

If ILO’s experts find that the law has been violated, they can write a report that will go public. However, no concrete sanction but « coercive mechanisms », according to Charles Autheman, can be imposed in case of non-compliance.

To help seaworkers deal with this crisis, a center for mental health assistance was set up last February in Saint-Nazaire, in the west shores of France.

For Camille Jego, clinical psychologist at the center, it is very difficult for sailors to face the unknown when it comes to their safe return to land. When you have time limits, a « dissociation » phenomenon helps you deal with the harsh realities of living at sea. But when these limits disappear, you may face a real psychological crisis.

As can your loved ones, waiting for your safe return. “Some families thought their relatives were dead because they didn’t have any more contact with them”. 21% of sailors questioned by Camille Jego are suffering from post-traumatic stress, a rate ten times higher than that of the general population.

By Alexis Souhard, Thomas Gropallo, Mathilde Rezki, Mathieu Michel, Baptiste Mougey and Erwan Morvan