Since 2018, a significant influx of migrant started coming to France through the Pyrénées-Atlantiques. And for the first time last years, 7 of them lost their lives in the Basque Country while attempting to take this route. A tragic end similar to that of the 4404 migrant deaths that were registered last year by the NGO Caminando Fronteras.

On October 14, 2021, at around 5 a.m., Mohamed Kemal, Fayçal Hamadouche and another Algerian migrants, asleep on a train rail, were killed by a TER near Saint-Jean-de-Luz. Their fourth companion was seriously injured. That is the end of one of many tragic stories of four migrants who attempt to cross the French-Spanish border illegally. Mohamed Kemal crossed the sea to Cartagena after leaving his hometownChlef. Fayçal Hamadouche left Al Hamra to reach Palma de Majorque by sea, then travelled there to Saragossa. Their path crossed that of their unfortunate and ephemeral companions in Irun, in Basque Country. This border town is the meeting point for many migrants who want to join France. Between January and August 2021, almost 4,100 people tried to cross the border illegally from Irun. A record number that keeps growing.

The vast majority of migrants attempting to reach Europe take the sea route. Today, Spain has become the first country of access to the European continent for migrants, well before Italy and Greece who topped the list a few years back. In 2016, Spain accounted for only 3.4% of total migrant arrivals in Europe. Far behind Greece and Italia. In four years, the situation has been completely reversed, as the Iberian Peninsula is now the preferred route for migrants, accounting for 42% of the flow, compared to 34.3% for Italy and 14.8% for Greece.

A hazardous journey

To reach Spain, four main roads exist for migrants. The first one is via Alboràn. It links the Moroccan Rif to the Andalusian coast. Most migrant who chose this path are Moroccan, Ivorian and Algerian. They embark on the Moroccan coast between Al Hoceima region and Nador. Several arrival destinations are then possible: the Spanish military enclaves on the African continent (Island of Mar, Tierra, Zaffarines…), the city of Melilla or the Andalusian coast.

East of the Alborán route is the Algeria road. Mainly used by natives, they leave from the western coast and they try to reach the Almeria coast, the Balearic Islands or the Valencia region. The four Algerian migrants, victims of the train accident in Saint Jean de Luz, took this route.

The Strait of Gibraltar is an historical path for migrants. From this point, only 14 km separate the two continents. Migrants using this route are mostly from Morocco and sub-Saharan communities. They embark along the northern coast of Morocco from the seaside resort of Moulay Bousselham to the Spanish autonomous city of Ceuta, which borders Morocco.

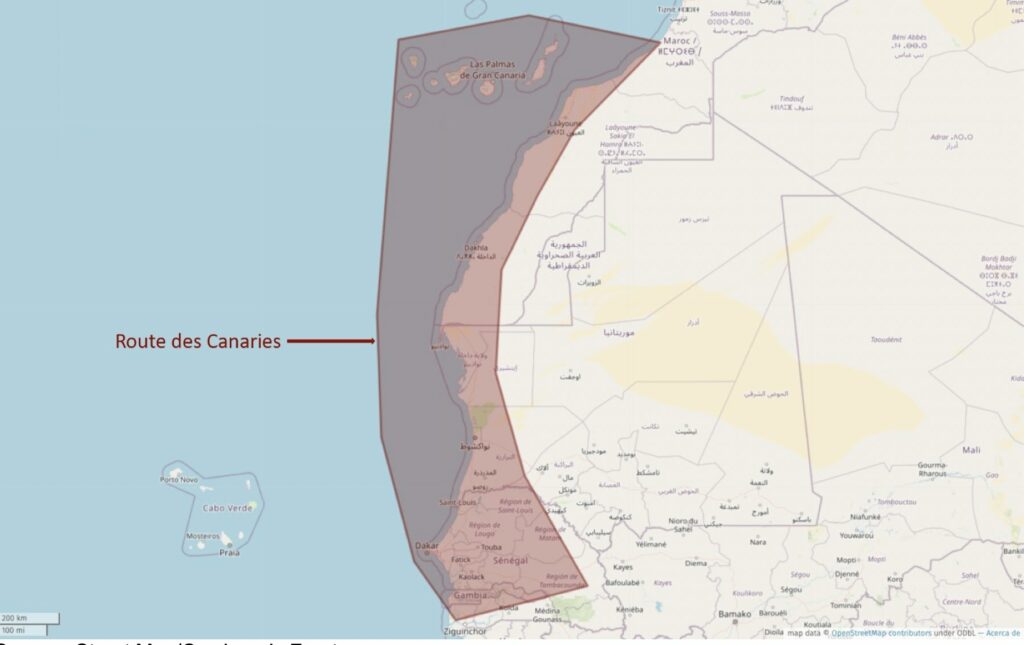

The last route is that of the Canary Islands. It is the most dangerous one but also the one that is followed by most migrants. According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, 25,000 people embarked on makeshift boats from Morocco, Senegal, Mauritanie or Gambie to the Canary Islands in 2020. This route is mainly used by migrants from Mali, Côte d’Ivoire, Senegal, Guinea, Morocco, Cameroon, Gambia and the Comoros. On September 24 2021, a pirogue with 50 sub-Saharan migrants (30 women and 8 children) left Daklha in Morocco to reach the Canary Islands. Migrants got lost at sea. On Facebook, the association “Protégons les migrants, pas les frontiers” announced that there were only five survivors from this tragedy. When they got news that the boat sunk, it was already too late.

In 2021, 4404 migrants died on these routes, according to the NGO Caminando Fronteras, with 4016 just on the Canary Islands route. It was the deadliest year for migrants trying to join Spain.

Source: Street Map. ©Caminando Fronteras.

Source: Street Map. ©Caminando Fronteras.

Source: Sud Ouest 20/10/2021

First deaths in the Basque Country

Abdoulaye Coulibaly, a 18-year-old Guinean, tried to join his uncle in Nantes. He left Dakhla in Morocco and arrived in the Canary Islands on May 23, 2021, before being placed in a migrant center at Granollers in Catalonia. On 5 August, he reached Irun but drowned three days later in the Bidasoa River on the French-Spanish border. Atlantic Pyrenees are one of the main routes for refugees from Africa. Since 2018, local associations estimate that more than 25,000 refugees have passed through Bayonne.

Many migrants of different nationalities pass through Irun. On Facebook, publications announcing that migrants’ passports have been lost at the Irun Red Cross camp are growing. On 9 November, it was that of Diop Souleymane, a Senegalese national who probably passed through Morocco to reach the border town. Three days later, those of Marrakchi Mahdi, a Tunisian, and Sow Mamadou Alpha, a Guinean, were found. These three are examples of migrants who crossed the sea and then Spain to end up in Irun before continuing their journey. As a result, police checks have been reinforced at the various crossing points between Irun and the French Basque Country.

Abdoulaye Coulibaly, a 18-year-old Guinean, tried to join his uncle in Nantes. He left Dakhla in Morocco and arrived in the Canary Islands on May 23, 2021, before being placed in a migrant center at Granollers in Catalonia. On 5 August, he reached Irun but drowned three days later in the Bidasoa River on the French-Spanish border. The Atlantic Pyrenees is one of the main routes for refugees from Africa. Since 2018, local associations estimate that more than 25,000 refugees have passed through Bayonne.

Many migrants of different nationalities pass through Irun. On Facebook, publications announcing that migrants’ passports have been lost at the Irun Red Cross camp are growing. On 9 November, it was that of Diop Souleymane, a Senegalese national who probably passed through Morocco to reach the border town. Three days later, those of Marrakchi Mahdi, a Tunisian, and Sow Mamadou Alpha, a Guinean, were found. These three are examples of migrants who crossed the sea and then Spain to end up in Irun before continuing their journey. As a result, police checks have been reinforced at the various crossing points between Irun and the French Basque Country.

To escape controls, migrants swim across the Bidasoa. Some drown, like Abdoulaye Coulibaly or Yaya Karamoko who was the first to die in the river while trying to cross the French-Spanish border in the Basque Country. On November 20, 2021, the Facebook page « Protégons les Migrants, Pas les Frontières” announced the death of Billal Said, an Ivorian man in his forties who was found in the Bidasoa River.

Other migrants try to reach the Bayonne station on foot, walking along the railway, and thus risking their lives. The three Algerian migrants hit by a TER in Saint-Jean-de-Luz in October are victims of this strategy. In total, seven migrants died in the French Basque Country in 2021.

Once they arrive to Bayonne, some continue their journey by bus where controls are occasional. Most go north, in particular to Paris but some choose to stop their journey in the Basque Country, like Guillaume who came from the Ivory Coast on a raft three years ago and is now an apprentice baker.

Lack of European response

Some of these stories are narrated on social networks. Losseni Fofana left the Ivory Coast with the aim of settling in France. During his long journey, he crossed the strait of Gibraltar to reach the Spanish Coast rowing aboard a zodiac g. In spring 2019, he arrived to Saint-Jean-de-Luz, in France. There, he met the owner of a restaurant, Komptoir des amis who decided to hire him and help him obtain a cooking certificate. Losseni hopes that one day he will set up his own restaurant here in the Basque Country, his new home.

The president of the Spanish Basque government, Iñigo Urkullu Renteria, and his French counterpart, Jean-René Etchegaray, say they are « overwhelmed » by the sudden influx of migrants. Camps like the Pausa centre in Bayonne, and border controls are not enough to manage the arrivals. They want the European Union and its Member States, « to secure the passage of these migrants in transit ». For now, their plea has not yet been answered.

Maxime Asseo, Hugo Bouet et Maxime Dubernet de Boscq

BLACK BOX

For this investigation, we first carried out a broad survey of reports as well as articles from French, Spanish (El Pais), and English (BBC) newspapers, in order to have a better understanding of the migration routes. We looked into the crossing at the French-Spanish borders as Spain has become the epicenter of illegal African migration to Europe .

Media : La Croix, Le Monde, Le Figaro, La Dépêche, Courrier International, Le Parisien, France Inter, RTBF, Atlantico, InfoMigrants.

This was supplemented by reports and studies published by NGOs, including Caminando Fronteras. Two of the NGO’s public reports were particularly useful in providing figures: “Après la frontière” et “Suivie du droit à la vie à la frontière occidentale euro africaine. Année 2021 ». The maps produced by the NGO also helped us to understand the four routes that migrants take to get to Spain. To know concretely where their journey started from Africa and where they arrived in Spain.

But also data verification through official institutions : Instituto Nacional de Estadistica, Statistiques sur la migration vers l’Europe – Commission Européenne, Comisión Española de Ayuda al Refugiado | CEAR, Insee, ACNUR – La Agencia de la ONU para los Refugiados, Frontex European Union Agency.

We decided to carry out a wide-ranging survey of articles on the Basque Country : Sud Ouest, La République des Pyrénées, Mediabask, France 3 Pays Basque, France Bleu Pays Basque. A lot of information was scattered in the local press.

We were interested in social networks to trace the itinerary of migrants. On Facebook and instagram, we came across several facebook pages tracing the history of migrants: the association « Elkartzsuna Larrun« , « Collectif Diakité« , « Protégeons les migrants, pas les frontières« . All of them told their daily lives as an association, but also described stories via posts. This is how we got a start on tracing the paths of Billal Said, DIop Souleymane, Abdoulaye Coulibaly and Yaya Karamoko. The personal profiles of these migrants allowed us to discover their stories. The Facebook page of Marie Cosnay, an activist for the reception of migrants based in Bayonne, gave many details.

On Instagram, we discovered « quedelabouche« , a page of a restaurant owner that featured the testimony of Losseni Fofana.

Twitter searches were futile. The keywords did give us results about migrants, but never with names. The few accounts found were empty of tweets and images.

We tried to use Jeffrey’s Image Metadata Viewer to track down images of migrants found on social networks, without success. We were unable to obtain the location of any of them, to our great regret. Similarly, there was no data relevant to our topic on Migration Policy Data Hub, Vital Record Search Tools or MixedMigration. With Fatmap, we were able to observe in detail the routes of migrants in the Basque Country, and the geological difficulties.