In 2016, the presidential election shined a light on a new threat: fake news. Still today, some shadows remain on how president Trump was elected and how fake news affected Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump’s campaigns.

With the emergence of social networks, anybody can share the information they want, or believe in. Those using social media to favor one candidate or another have something in mind, such as making money or gaining political influence.

“All of the major networks and news outlets, newspapers, etc., have incorporated fact-checking into their coverage”, says Lucas Graves, an assistant professor at the School of Journalism and Mass Communication at the University of Wisconsin. “It’s an accepted and widely established feature of campaign coverage and the primaries or general elections”.

As the 2000s ushered in new technologies, more than 50 fact-checking websites were created in the U.S. Only a third of them are nationwide. Most of them are focused on one state or one region. “Fact-checking has become much more normalized over the last ten or fifteen years but I haven’t seen people sorting out new or innovative fact-checking”, said Lucas Graves, also author of the thesis “Deciding what’s true, The rise of political fact-checking in American journalism”. Usually connected to one media or state, they try to debunk misinformation on the web. They do not usually focus on politics, but the primaries are forcing them to come back to these issues.

So far, six debates have taken place, each time narrowing the number of candidates. The next one will take place on January 14th. Five candidates will take part of this event where ideas and convictions are essential. But other weapons are also needed.

Numbers & sound bites

Debates are a special moment to express ideas to a large audience. And as each candidate wants to be more convincing than the other, they pull out all the stops using strong arguments that are sometimes untrue.

That is why CNN and other large media outlets started “live checking” the shows. Sound bites and numbers are fact-checked in real time in order to enlighten the audience. In contrast with politicians who want to rally people, journalists take time to explain the context surrounding a fact or specify the meaning of a number.

A lot of TV channels use their website to live-check. A number of newspapers are placing themselves on the second line of fact-checking. They go deeper into the subjects brought up during the debates and on social media.

During the sixth debate, which took place on December 19th, hosted by PBS and Politico, CNN noticed nine approximate statements. For instance, Joe Biden claimed that he respected the law by receiving a largest contribution of $2,800. He was correct but he didn’t mention that he was also backed up by a super PAC (Political Action Committee).

.@JoeBiden notes the largest contribution he’s accepted is the maximum allowed under law at $2,800. Left unsaid is that he’s the only one onstage with a super PAC funded by wealthy donors supporting him.

— Michelle Ye Hee Lee (@myhlee) December 20, 2019

These initiatives need time and training. That’s why a lot of specialized websites have emerged: Factcheck, Checkyourfact, Snopes or Politifact. They aim is to produce truthful and enlightened information. Comprised mainly of former journalists, they use more or less the same tools as traditional media to gather information, investigate and write. Having learned the lesson of the 2016 campaign, the media has diversified their tools. Not only through fact-checking projects but also by using scales and ratings to evaluate news circulating on the web.

Fighting new threats

As journalists, they also have a look at what information is spread on social media. This is because fake news can also be entirely fabricated by people outside of the spotlight. This is the third line of fact-checking. And as fake news usually plays on people’s emotions, they spread wildly on social networks, especially Facebook who only recently recognized their idole they played in Trump’s election.

The FBI recently released a document stating that the thread of misinformation lies inside the US. For instance, the allegation regarding Pete Buttigieg who was accused of sexual assault last week was made up by American white nationalists.

Since 2016, the fight against fake news has been reinforced but the threat itself has found new ways to interfere in politics. That is why Facebook now uses a task force to eradicate fake news from its platform.

But a lot of bots and “trolls” still use Facebook or Twitter to influence voters one way or another. And the most dangerous part is that they now know they can actually have an impact.

Since the beginning of the democratic primaries, Kamala Harris and Joe Biden have been the most frequent targets of fake news, according to VineSight, who tracks Twitter activity. Kamala Harris was particularly affected by racist campaigns against her.

As said earlier, fake news is evolving as fast as fact-checking is. Now, “troll” are smarter and look more like humans and Fake pages and fake communities are created on a daily basis.

If Twitter and Facebook are fighting back, unfortunately 4chan and Reddit are less effective.

Last but not least, one of the main risks for the next election would be deep fakes : videos and content made by AI to distort reality. One of the main examples is the video of Nancy Pelosi broadcast last year. “Deep fakes have been somewhat overhyped even if the fake is obvious. It draws the media’s attention and make headlines even if it’s debunked”, says Lucas Graves.

Fact-checking the fact-checkers

According to a survey conducted from February to March 2019 by the nonpartisan Pew Research Center and released in June 2019, nearly half of the questioned Americans (48%) believe fact-checkers favor one political party. But this trend mostly appears with Republicans : the survey reveals that around 70% of Republicans to 29% of Democrats think fact-checkers are biased and favor one political party. Conversely, 69% of Democrats and barely 28% of Republicans consider that fact-checkers deal fairly with all political sides. Among all the questioned Americans during the survey, it turns out that 47% of political independents say that fact-checkers tend to favor one side, against 51% reckoning they deal fairly with all sides.

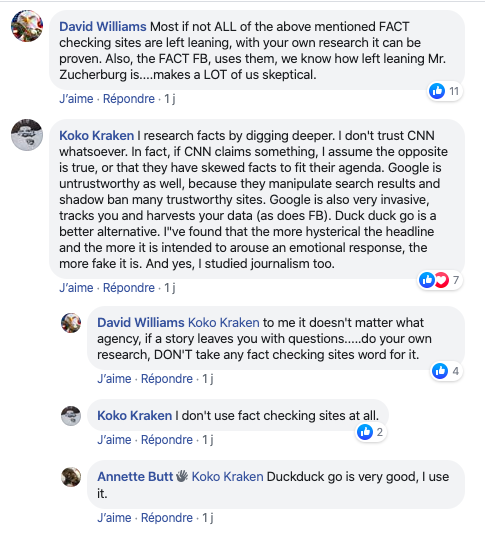

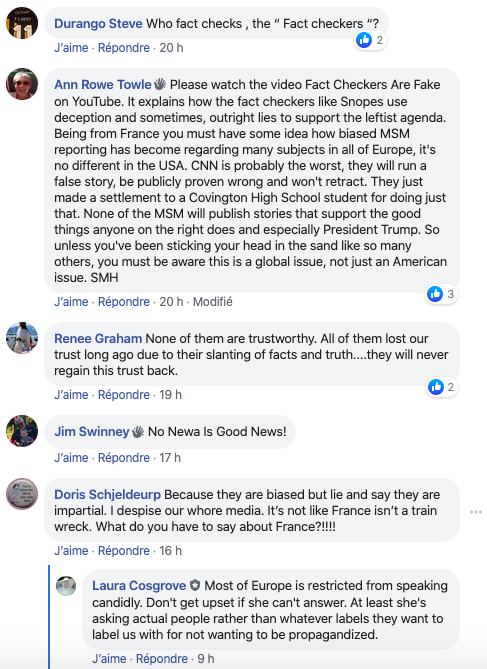

This assessment appears on social media where some people have decided to create groups in which they can fact-check news on their own and “prove the fact-checkers are wrong”. It’s the case for the Facebook community called “Fact-checking the fact-checkers”. This group does not claim any political affiliation, but the members often perceive fact-checkers as “left leaning sites”. This political orientation “makes a lot of us skeptical”, claims David Williams, one of the Facebook group members. “In fact, if CNN claims something, I assume the opposite is true, or that they have skewed facts to fit their agenda”, says another member.

In fact, most of the group members have decided only to inform themselves. “To me, it doesn’t matter what agency, if a story leaves you with questions… do your own research, don’t take any fact-checking sites word for it.”

This is a trend that has been confirmed by the Pew Research Center’s survey. The report explains that “even as Americans express concerns about fact-checkers, they have mixed confidence in their own ability to check the facts of news stories”. A third say they are very confident in their ability to check the accuracy of news story.

“I research facts by digging deeper. I learnt how to ferret out the truth long before fact-checkers and even the internet existed. I stopped believing internet content as every idiot in the world had access to internet, confusing their opinions with fact, editorial content posing as news”, says David Williams.

Some others use the term “propaganda”. ”So called fact-checking is subjectivity parsed elements of phrases to represent whatever the fact-checker wants ! Basically propaganda”.

The journalists learnt lessons from the 2016 presidential elections. Fact-checkers evolved to fill the gap. But will they be enough prepared for the upcoming election time?

Laura Diab, Julie Chapman and Félicie Gaudillat